I have begun to contact different Civil War Societies and sharing my blog in hopes of sharing information about Cist history. I am more interested in finding human connections and stories rather than finding material relics about Cist history, but I will look at material findings to help make more connections. I recently found a pistol that belonged to Henry M. Cist on the internet.

I am contacting War Between the States, P. O. Box 267, Lady Lake, FL 32158.

Charles Cist and his descendants are the focus of research from Pewabic Writing. The research findings include how Charles Cist changed his name before he arrived to the British Colonies from St. Petersburg, Russia. There is an additional viewpoint that illustrates a common theme of liberty, freedom, and justice. American and global ideals that span from the American Revolution to modern present day society are explored. Pewabic Writing invites you to comment and join to press follow button.

Tuesday, November 19, 2013

Thursday, November 7, 2013

Response from Dr. Wulf von Restorff

In June of 2013 I emailed a request for information at the genealogy department in Germany about Charles Cist. This is my response.

Good Afternoon,

The DAGV is Academic Council of German Genealogical Association. Its purpose is the lobby work for the German family researchers and the coordination of genealogical research. It has no resources; no own library , data files or collections of charters, and it executes no research by order. The support given by the organization is very restricted and consists only as and advice to direct enquirers.

So, I can recommend to search Google, Family Search, Ancestry, My Heritage, or GedBas.

Dr. Wulf von Restorff

I interpret this as though I am at a dead end on this, but I will keep trying different avenues. I replied with a follow up email to Dr. Wulf von Restorff to keep Charles Cist in mind when networking. I wish him well.

I continue to network and find different avenues to pursue. I have signed up for the December 4th American History Conference of the Smithsonian Museum at the Warner Bros. Theater in Washington D.C.

It is acceptable to find artifacts on the Cist family. I am more interested in photographs taken and letters written by Cist family members than finding material items that belonged to Cist members.

I have written War Between the States at P.O. Box 267, Lady Lake, FL 32158. Perhaps, this company may have photos of Cist members that are unidentified. If they look at this blog they may match photos to names.

Good Afternoon,

The DAGV is Academic Council of German Genealogical Association. Its purpose is the lobby work for the German family researchers and the coordination of genealogical research. It has no resources; no own library , data files or collections of charters, and it executes no research by order. The support given by the organization is very restricted and consists only as and advice to direct enquirers.

So, I can recommend to search Google, Family Search, Ancestry, My Heritage, or GedBas.

Dr. Wulf von Restorff

I interpret this as though I am at a dead end on this, but I will keep trying different avenues. I replied with a follow up email to Dr. Wulf von Restorff to keep Charles Cist in mind when networking. I wish him well.

I continue to network and find different avenues to pursue. I have signed up for the December 4th American History Conference of the Smithsonian Museum at the Warner Bros. Theater in Washington D.C.

It is acceptable to find artifacts on the Cist family. I am more interested in photographs taken and letters written by Cist family members than finding material items that belonged to Cist members.

I have written War Between the States at P.O. Box 267, Lady Lake, FL 32158. Perhaps, this company may have photos of Cist members that are unidentified. If they look at this blog they may match photos to names.

Monday, November 4, 2013

Letter to the American History Department at the Smithsonian Museum

Charles Cist, Philadelphia printer, was involved with the American Revolution. His descendants were involved with the American Civil War. I find myself involved with the digital revolution. Here is a letter written to Mr. John A. Fleckner, senior archivist, at the Smithsonian Museum. It is an intention to network and involve myself with a continuation movement of combining and finding lost Cist family papers to bring about an added view point to American history. It is my belief that by finding the lost Cist family papers it will add to the American experience.

November 4, 2013

Mr. John A. Fleckner

Senior Archivist

Smithsonian Museum

National Museum of American History

Kenneth E. Behring Center

14th Street and Constitutional Avenue NW

Washington, DC 2001

Dear Mr. Fleckner,

I have signed up for the December 4th conference to network and get involved with the Society of American Archivists.

In the daily course of life, reading articles, networking, and applying an interdisciplinary approach to adding to the American experience, I am asking that you take note of Charles Cist, a Philadelphia printer during the American Revolutionary War period. I have done research on Mr. Cist and my findings have concluded that the history books have omitted the fact that Mr. Cist was not only a printer of the Continental Congress, but he was also a treasurer of the Continental Congress. As a direct descendant of Charles Cist, I wish to share with your department my documentation of Continental currency signed by Charles Cist

Oral history is a valid form of communication. If your department is interested in my oral presentation about the life of Charles Cist, I am at your disposal.

Thank you for your time. Perhaps we can met on December 4th at the conference.

Sincerely Yours,

Andrew C. Allen

November 4, 2013

Mr. John A. Fleckner

Senior Archivist

Smithsonian Museum

National Museum of American History

Kenneth E. Behring Center

14th Street and Constitutional Avenue NW

Washington, DC 2001

Dear Mr. Fleckner,

I have signed up for the December 4th conference to network and get involved with the Society of American Archivists.

In the daily course of life, reading articles, networking, and applying an interdisciplinary approach to adding to the American experience, I am asking that you take note of Charles Cist, a Philadelphia printer during the American Revolutionary War period. I have done research on Mr. Cist and my findings have concluded that the history books have omitted the fact that Mr. Cist was not only a printer of the Continental Congress, but he was also a treasurer of the Continental Congress. As a direct descendant of Charles Cist, I wish to share with your department my documentation of Continental currency signed by Charles Cist

Oral history is a valid form of communication. If your department is interested in my oral presentation about the life of Charles Cist, I am at your disposal.

Thank you for your time. Perhaps we can met on December 4th at the conference.

Sincerely Yours,

Andrew C. Allen

Sunday, October 27, 2013

This next blog entry illustrates new knowledge for me that Charles Cist printed a journal of an early balloonist in Philadelphia in 1793. Please look at this link.

Thanks to Mr. David K. Frasier at the Lilly Library.

Thanks to Mr. David K. Frasier at the Lilly Library.

Wednesday, July 3, 2013

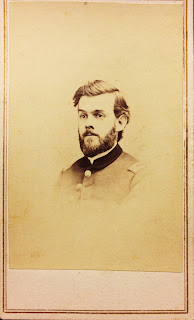

Henry M Cist portraits

Henry M Cist as Colonel in Nashville, July 1865.

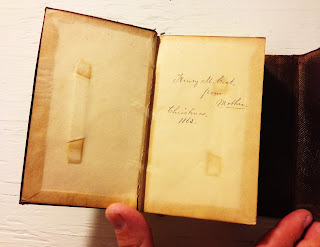

Bible given as gift to Henry M Cist from his mother as he went to war.

Henry M Cist taken later in life as he authored The Army of the Cumberland.

Wednesday, June 26, 2013

Portrait of Henry M Cist circa 1880

Henry M Cist was a Brigadier General in Civil War and author of Army of the Cumberland, and served as director of the Chickamauga Memorial Association in 1889. Photo from private collection.

Additionally, Mr. Cist returned from the American Civil War and returned to his homestead in College Hill, Cincinnati, OH in 1866. In 1869 he was elected corresponding secretary of the Society of the Army of the Cumberland (Army of the Cumberland New York: Scribner's Sons). It was among the first written accounts of that battle. He also wrote about his other friends who were in the Civil War with him. He wrote a biography of The Life of General George H. Thomas.

Finally, as the later part of his life took place, he was instrumental in preserving Civil War battlefields. Congress authorized the Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park in 1890. Mr. Cist was a director in 1889. In 1892 he served as president of the Ohio Society, Sons of American Revolution.

Mr. Henry M. Cist died of pneumonia while touring Italy at age 63. He was buried at Spring Grove Cemetery, Cincinnati, OH, 1902.

born February 20, 1839 Died December 16, 1902.

Based on family stories. It is my conclusion that when the Cist family went to Europe at the turn of the century, they were visiting cultural institutions that placed winning bids on the Lewis J. Cist autograph collection. Henry Cist was making further connections to the causes of freedom and the fact that he died in Italy is a clue for me to do continued research. He died before he could write down his findings.

Saturday, June 22, 2013

The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America Part III

An additional note on early government printing seems in order here. The one obvious point is that government printing was done in cities other than first Philadelphia and later Washington. For example, in 1798, the majority of the 147 assigned government imprints belonged to Philadelphia firms-William Ross, John Fenno, Joseph Gates, and Way and Groff. But in New York (Louis Jones), Baltimore (William Pechin), Boston (John Russell), and Providence (Carter and Wilkinson), government contract printing was done.

Cist's government printing was more than likely in the same vain as his earlier work with Steiner for the Pennsylvania assembly-paper, forms, and other miscellaneous printing. Since his imprint appeared on two editions of postal regulations, it may be safe to assume the same would be true for any of his other federal publications, although he may have done job printing for the Post Office Department. Another reason to suspect the level of Cist's government printing is the number of competitors who began to flood the new capital, including the aforementioned Way and Groff, Samuel Harrison Smith, and William Duane. If imprints appeared on government publications, it was usually the imprint of Duane after 1800. McMurtrie concludes that as of 1802, "there was no one government printer."19 Finally, the DAB entry for Jacob Cist mentions only that Jacob managed his father's Washington office, which "was forced to close by reason of the change in federal administration,"20 when Adams left office in 1801. Thus, we can conclude that, lacking concrete evidence, the DAB entry on Cist is incorrect.

There are other sources which help to fill in gaps on the printing career of Charles Cist. The 1790 census sheds some significant light on the extent of his business.21 His household consisted of two males over age sixteen (one was Cist), six males under age sixteen (one was his older son), and eight females (one of whom was his wife). Simple mathematics leaves at least fifteen unidentified individuals living in the Cist household-six of whom were males. From McCulloch's Additions we find that Conrad Zentler was an apprentice to Cist. Certainly, some of the six males living under Cist's roof were also apprentices; thus, we have an idea that Cist ran a sizable printing operation. The 1800 census shows the Cist household consisted of two males in the fifteen to twenty-six age range and seven females, not counting his wife. Since Jacob was probably in Washington City and young Charles was only eight, this too probably represents apprentice printers.22 We can also find some idea of what the printer charged for his work. His proposal to print Congressional journals (1785) was for 1000 copies at 610 shillings and 5 shillings for binding per volume.23 a 1784 bill shows Cist charged 53 shillings 8 pence for printing blank bills (1,728 large bills or 3,456 smaller bills). These few examples also help to illustrate that Cist's margin of profit did not depend on book printing-instead , like most others of his trade, Cist made money on printing paper, blank forms, stationery, and assorted printing assignments. In contrast, the Congressional Commissioners of Accounts had earlier cited Steiner and Cist as being extravagant in their charges. In question was a L200 charge in 1779 for printing a broadside (Evans 15966) in German for the call of a constitutional convention. Five thousand copies of the circular were printed in 1778. Congress also registered its dissatisfaction with the charges of another Philadelphia printer, David Claypoole. This perhaps was one of the factors considered in 1785 when the Continental Congress did not select Cist to print its journals. We also know that Cist did not operate a book store at his printing shop as many other early printers did. No single Evans entry indicates Cist sold what he printed.24

We do know Cist moved some aspect of his business to Washington by 1800, although , according to McCulloch, Cist printed for the post office before the government moved to the new capital city. McCulloch says Cist moved the English part of his printing to Washington. Cist must have had considerable work: McCulloch reports that the printer built two or three houses there. Cist sold his presses and much of the rest of his office in Washington. This is borne out by the scattered Cist imprints after 1800-only two other than the almanac. All of his printing after 1800 carried a Philadelphia imprint.25

Cist's government printing was more than likely in the same vain as his earlier work with Steiner for the Pennsylvania assembly-paper, forms, and other miscellaneous printing. Since his imprint appeared on two editions of postal regulations, it may be safe to assume the same would be true for any of his other federal publications, although he may have done job printing for the Post Office Department. Another reason to suspect the level of Cist's government printing is the number of competitors who began to flood the new capital, including the aforementioned Way and Groff, Samuel Harrison Smith, and William Duane. If imprints appeared on government publications, it was usually the imprint of Duane after 1800. McMurtrie concludes that as of 1802, "there was no one government printer."19 Finally, the DAB entry for Jacob Cist mentions only that Jacob managed his father's Washington office, which "was forced to close by reason of the change in federal administration,"20 when Adams left office in 1801. Thus, we can conclude that, lacking concrete evidence, the DAB entry on Cist is incorrect.

There are other sources which help to fill in gaps on the printing career of Charles Cist. The 1790 census sheds some significant light on the extent of his business.21 His household consisted of two males over age sixteen (one was Cist), six males under age sixteen (one was his older son), and eight females (one of whom was his wife). Simple mathematics leaves at least fifteen unidentified individuals living in the Cist household-six of whom were males. From McCulloch's Additions we find that Conrad Zentler was an apprentice to Cist. Certainly, some of the six males living under Cist's roof were also apprentices; thus, we have an idea that Cist ran a sizable printing operation. The 1800 census shows the Cist household consisted of two males in the fifteen to twenty-six age range and seven females, not counting his wife. Since Jacob was probably in Washington City and young Charles was only eight, this too probably represents apprentice printers.22 We can also find some idea of what the printer charged for his work. His proposal to print Congressional journals (1785) was for 1000 copies at 610 shillings and 5 shillings for binding per volume.23 a 1784 bill shows Cist charged 53 shillings 8 pence for printing blank bills (1,728 large bills or 3,456 smaller bills). These few examples also help to illustrate that Cist's margin of profit did not depend on book printing-instead , like most others of his trade, Cist made money on printing paper, blank forms, stationery, and assorted printing assignments. In contrast, the Congressional Commissioners of Accounts had earlier cited Steiner and Cist as being extravagant in their charges. In question was a L200 charge in 1779 for printing a broadside (Evans 15966) in German for the call of a constitutional convention. Five thousand copies of the circular were printed in 1778. Congress also registered its dissatisfaction with the charges of another Philadelphia printer, David Claypoole. This perhaps was one of the factors considered in 1785 when the Continental Congress did not select Cist to print its journals. We also know that Cist did not operate a book store at his printing shop as many other early printers did. No single Evans entry indicates Cist sold what he printed.24

We do know Cist moved some aspect of his business to Washington by 1800, although , according to McCulloch, Cist printed for the post office before the government moved to the new capital city. McCulloch says Cist moved the English part of his printing to Washington. Cist must have had considerable work: McCulloch reports that the printer built two or three houses there. Cist sold his presses and much of the rest of his office in Washington. This is borne out by the scattered Cist imprints after 1800-only two other than the almanac. All of his printing after 1800 carried a Philadelphia imprint.25

Friday, June 21, 2013

The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America Part II

4. William McCulloch, "Additions to Thomas's History of Printing," Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society, 31 (April 1921), 203.

5. Pennsylvania Colonial Records (Philadelphia: J. Severns, 1851-1853), XI, 319; Pennsylvania Colonial Records, XII, 404, 440, 448, 456. The mention of monetary units (dollars or pounds) is risky business considering the inflationary nature of currency in revolutionary America. The figures are cited for illustrated purposes - any discussion of the real value of the pending dollar would lengthen this brief essay beyond the percentage scope.

6. U.S. Continental Congress, Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789 (Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1904-1937), V, 829; VI, 996 ; VII, 325; XIII, 421: XIV, 550, 754: XV, 1241.

7. The information on the office location of Steiner and Cist and for Cist is from the directory of publishers in Charles Evans, American Bibliography: A Chronological Dictionary of all books, Pamphlets, and Periodical Publications Printed in the United States of America from the Genesis of Printing in 1639 Down to and including the Year 1800 (New York: Peter Smith, 1941-67) for the various years of operation. See also Joseph Sabin, Bibliotheca Americana. A Dictionary of Books Relating to America; From Its Dictionary to the Present Time (New York: Bibliographical Society of America, 1868-1936). Much of this was also published in H. Glenn Brown and Maude O. Brown , A Directory of the Book-arts and Book Trade in Philadelphia in 1820; including Printers and Engravers (New York: New York Public Library, 1950); see also McCulloch , "Additions," AAS Proceedings, pp.95, 202.

8. The descriptive statistics included in this paper are derived from the various volumes of Evans (volumes 5-14) after a careful hand -counting of Cist and Steiner and Cist imprints. This was supplemented with OVLC RLIN by searching for printers to verify any questionable entries or those about which Evans was not sure. Newspaper and almanac entries were also verified in Oswald Seidensticker, The First Century of German Printing in America , 1728-1830 (Philadelphia: Schaefer and Koradi, 1893).

9. See Richard B. Sealock, "Publishing in Pennsylvania, 1785-1790," master's thesis, Columbia University, 1935; the Columbian Magazine was published for several years under various titles.

10. Isaiah Thomas, The History of Printing in America with a Biography of Printers and an Account of Newspapers (New York: Weathervane Books, 1970), pp. 404-05; McCulloch, "Additions," AAS Proceedings, p. 204; Douglas C. McMurtrie, A History of Printing in the United States: The Story of the Introduction of the Press and of Its History and influence during the Pioneer Period in Each State of the Union (New York: B. Franklin, 1969), pp. 67, 268-70. Continue with the article...

Also considered were proposals by printers James Adams, John Dunlap, Henry Miller, Robert Aitken Eleazer Oswald, Francis Childs, and Benjamin Wheeler: Dunlap was awarded the lucrative printing job.11 Cist had done some work for Congress , though; he was due $418 in 1778 for making paper and about $150 for printing 22,228 sheets of loan certificates in 1786. In 1778 he was reimbursed for expenses incurred on a trip to Baltimore. He, along with another Philadelphia printer, James Claypoole, apparently did some printing work. In 1785, he printed a four-page outline by William Barton for the establishment of a mint (Evans B6136).12

A letter from Pickering to the President of Congress, Elbridge Gerry, in 1785 is the strongest evidence of Cist's reputation. Supporting his fellow Philadelphian's printing proposal to Congress, Pickering referred to Cist's "ingenuity and worth" and high integrity. Pickering wrote:

Indeed, I know not any one so proper to be the printer to the United States. For he is not a mere printer; but a man of letters. The English and German languages are familiar to him- he understands the French- and he has that acquaintance with the dead languages which is acquired by a liberal education. With these qualifications, he possesses great modesty and obliging manners. Such a character needs only to be known to receive from you all the countenance and encouragement which his own merits and the public good shall require.13

While Pickering's efforts on behalf of Cist did not result in a successful government contract, he did recommend the printer to Webster. In March of 1792, Webster wrote to Pickering , "I highly approve of your employing Mr. Cist to print the Prompter, and cannot say his terms are unreasonable."14 The future Secretary of State had told Webster to consult with printers Bache, Joseph Crukshank, John Fenno, and Bailey for estimates for the job, and Cist was selected. In November, Webster wrote Pickering that Cist had forwarded $50 for sale of the Prompter (Evans 25006).15 Pickering's advocacy of Cist for government printing and Webster's satisfaction help future to establish Cist's status among the printers of early America.

Cist's printing activities for the rest of the eighteenth century included well over 125 separate titles. Although many were pamphlets, broadsides, or booklets, the majority were book-length. A careful analysis, using Evans and Sabin as authorities, reveals interesting results, and although there is little available research with which to compare Cist's printing, the data provide a microcosmic look at one printer's output.16 Statistically (using standard sources), Cist printed an almanac, a Bible, three books, and one short book in 1787. These statistics remained fairly consistent for the next several years- two books in 1782, four in 1783, four in 1784, and two in 1785. Interspersed during the first five years of his business were numerous broadsides and similar publications. In 1786, Cist's printing included six book-length works and five brief jobs, ranging from sixteen to forty pages. This trend continued on an annual basis until 1800, the year Cist opened a printing office in Washington. One steady imprint was the aforementioned German-language almanac. In addition, Cist printed George Frederich Wilhelm (Baron von Steuben's Regulations for the Control of the Troops of the United States (originally printed by Steiner and Cist in 1779 in a press-run of approximately 3,000 copies) seven times between 1782 and 1800 (Figure 1). He printed several agricultural treatises by noted husbandry man John Beale Bordley (Evans 26681, 26682, 30303, 31846, 33435, 35217, B10242), a New England primer (Evans 32529), a University of Pennsylvania Latin grammar (Evans 36309), and Webster's Primer (Evans 25006).

Cist's German-language printing is the most interesting aspect of his career (Figure 2). His imprint on these German titles indicated "Gedrucktbey Carl Cist," or printed by Carl Cist, Carl being the printer's given Russian name. Among his fifty-seven German-language imprints identified by Evans are a Bible (Evans 35201), Paine's Common Sense (Evans 14963) with Steiner, a German grammar (Evans 20938) printed simultaneously in English (Evans 20937), numerous works on religion, and a German edition of Steuben's Regulations (Evans 26361). But this represents only a portion of Cist's German printing. The recent publication of a revised The First Century of German Language Printing in the United States of America identifies an other eighty-one Cist imprints which escaped Evans and Sabin. The majority of these (sixty-two) are four-pages broadsides, but eleven of the German-language titles are more significant publications, ranging from thirty-two to 252 pages. From an examination of this German-language bibliography, Cist appears to be as important as any German printer from 1788 to 1795, seventy-nine German titles carried Cist's imprint. With his recognized language skills, Cist also printed a handful of titles in Latin and French.17

After 1800, Cist's printing decreased dramatically-generally he printed only the annual almanac and one other item from 1801 to 1805. These years represent the printer's opening a Washington office and introduce an inaccuracy in Cist's DAB entry.18 His biographer, Reginald C. McGrane, mentions that Cist was appointed public printer during the administration of President John Adams (1787-1801). This fact later emerged in the historical volume of Who Was Who, Appleton's Cyclopedia of American Biography, and several other biographical compilations. This inaccuracy is also cited in H. Benjamin Powell's Philadelphia's First Fuel Crisis, a history of the anthracite market in Pennsylvania. But neither Thomas nor McMurtrie make mention of Cist as a public printer, although both indicate he set up a printing operation in Washington. Leonard White's massive The Federalists: A Study in Administrative History, 1789-1801, makes no mention of Cist. In fact, there was no public printer until 1861. Cist did some government printing work, both in Philadelphia and later in Washington. Cist's imprint appeared on two copies of Post Office regulations, one printed in Philadelphia in 1798 (34904) and one in Washington in 1800 (38801). He undoubtedly contracted for other government printing, a powerful cog in the patronage machinery. For the 223 government imprints listed in Evans for 1799, 173 (77 percent) were unassigned. Only the postal laws (Evans 38801) carried Cist's imprint, and only twenty-five included a Washington imprint; Cist's and two other entries are the only ones assigned to a particular printer. The majority of the 173 unassigned entries were congressional bills or broadsides, and Cist more than likely contracted for some of this government work, but Cist was not the public printer.

I am categorizing information and I shall post it on up coming blogs.

Andrew C. Allen 6/21/13

513.638.7140

pewabic34@gmail.com

5. Pennsylvania Colonial Records (Philadelphia: J. Severns, 1851-1853), XI, 319; Pennsylvania Colonial Records, XII, 404, 440, 448, 456. The mention of monetary units (dollars or pounds) is risky business considering the inflationary nature of currency in revolutionary America. The figures are cited for illustrated purposes - any discussion of the real value of the pending dollar would lengthen this brief essay beyond the percentage scope.

6. U.S. Continental Congress, Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789 (Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1904-1937), V, 829; VI, 996 ; VII, 325; XIII, 421: XIV, 550, 754: XV, 1241.

7. The information on the office location of Steiner and Cist and for Cist is from the directory of publishers in Charles Evans, American Bibliography: A Chronological Dictionary of all books, Pamphlets, and Periodical Publications Printed in the United States of America from the Genesis of Printing in 1639 Down to and including the Year 1800 (New York: Peter Smith, 1941-67) for the various years of operation. See also Joseph Sabin, Bibliotheca Americana. A Dictionary of Books Relating to America; From Its Dictionary to the Present Time (New York: Bibliographical Society of America, 1868-1936). Much of this was also published in H. Glenn Brown and Maude O. Brown , A Directory of the Book-arts and Book Trade in Philadelphia in 1820; including Printers and Engravers (New York: New York Public Library, 1950); see also McCulloch , "Additions," AAS Proceedings, pp.95, 202.

8. The descriptive statistics included in this paper are derived from the various volumes of Evans (volumes 5-14) after a careful hand -counting of Cist and Steiner and Cist imprints. This was supplemented with OVLC RLIN by searching for printers to verify any questionable entries or those about which Evans was not sure. Newspaper and almanac entries were also verified in Oswald Seidensticker, The First Century of German Printing in America , 1728-1830 (Philadelphia: Schaefer and Koradi, 1893).

9. See Richard B. Sealock, "Publishing in Pennsylvania, 1785-1790," master's thesis, Columbia University, 1935; the Columbian Magazine was published for several years under various titles.

10. Isaiah Thomas, The History of Printing in America with a Biography of Printers and an Account of Newspapers (New York: Weathervane Books, 1970), pp. 404-05; McCulloch, "Additions," AAS Proceedings, p. 204; Douglas C. McMurtrie, A History of Printing in the United States: The Story of the Introduction of the Press and of Its History and influence during the Pioneer Period in Each State of the Union (New York: B. Franklin, 1969), pp. 67, 268-70. Continue with the article...

Also considered were proposals by printers James Adams, John Dunlap, Henry Miller, Robert Aitken Eleazer Oswald, Francis Childs, and Benjamin Wheeler: Dunlap was awarded the lucrative printing job.11 Cist had done some work for Congress , though; he was due $418 in 1778 for making paper and about $150 for printing 22,228 sheets of loan certificates in 1786. In 1778 he was reimbursed for expenses incurred on a trip to Baltimore. He, along with another Philadelphia printer, James Claypoole, apparently did some printing work. In 1785, he printed a four-page outline by William Barton for the establishment of a mint (Evans B6136).12

A letter from Pickering to the President of Congress, Elbridge Gerry, in 1785 is the strongest evidence of Cist's reputation. Supporting his fellow Philadelphian's printing proposal to Congress, Pickering referred to Cist's "ingenuity and worth" and high integrity. Pickering wrote:

Indeed, I know not any one so proper to be the printer to the United States. For he is not a mere printer; but a man of letters. The English and German languages are familiar to him- he understands the French- and he has that acquaintance with the dead languages which is acquired by a liberal education. With these qualifications, he possesses great modesty and obliging manners. Such a character needs only to be known to receive from you all the countenance and encouragement which his own merits and the public good shall require.13

While Pickering's efforts on behalf of Cist did not result in a successful government contract, he did recommend the printer to Webster. In March of 1792, Webster wrote to Pickering , "I highly approve of your employing Mr. Cist to print the Prompter, and cannot say his terms are unreasonable."14 The future Secretary of State had told Webster to consult with printers Bache, Joseph Crukshank, John Fenno, and Bailey for estimates for the job, and Cist was selected. In November, Webster wrote Pickering that Cist had forwarded $50 for sale of the Prompter (Evans 25006).15 Pickering's advocacy of Cist for government printing and Webster's satisfaction help future to establish Cist's status among the printers of early America.

Cist's printing activities for the rest of the eighteenth century included well over 125 separate titles. Although many were pamphlets, broadsides, or booklets, the majority were book-length. A careful analysis, using Evans and Sabin as authorities, reveals interesting results, and although there is little available research with which to compare Cist's printing, the data provide a microcosmic look at one printer's output.16 Statistically (using standard sources), Cist printed an almanac, a Bible, three books, and one short book in 1787. These statistics remained fairly consistent for the next several years- two books in 1782, four in 1783, four in 1784, and two in 1785. Interspersed during the first five years of his business were numerous broadsides and similar publications. In 1786, Cist's printing included six book-length works and five brief jobs, ranging from sixteen to forty pages. This trend continued on an annual basis until 1800, the year Cist opened a printing office in Washington. One steady imprint was the aforementioned German-language almanac. In addition, Cist printed George Frederich Wilhelm (Baron von Steuben's Regulations for the Control of the Troops of the United States (originally printed by Steiner and Cist in 1779 in a press-run of approximately 3,000 copies) seven times between 1782 and 1800 (Figure 1). He printed several agricultural treatises by noted husbandry man John Beale Bordley (Evans 26681, 26682, 30303, 31846, 33435, 35217, B10242), a New England primer (Evans 32529), a University of Pennsylvania Latin grammar (Evans 36309), and Webster's Primer (Evans 25006).

Cist's German-language printing is the most interesting aspect of his career (Figure 2). His imprint on these German titles indicated "Gedrucktbey Carl Cist," or printed by Carl Cist, Carl being the printer's given Russian name. Among his fifty-seven German-language imprints identified by Evans are a Bible (Evans 35201), Paine's Common Sense (Evans 14963) with Steiner, a German grammar (Evans 20938) printed simultaneously in English (Evans 20937), numerous works on religion, and a German edition of Steuben's Regulations (Evans 26361). But this represents only a portion of Cist's German printing. The recent publication of a revised The First Century of German Language Printing in the United States of America identifies an other eighty-one Cist imprints which escaped Evans and Sabin. The majority of these (sixty-two) are four-pages broadsides, but eleven of the German-language titles are more significant publications, ranging from thirty-two to 252 pages. From an examination of this German-language bibliography, Cist appears to be as important as any German printer from 1788 to 1795, seventy-nine German titles carried Cist's imprint. With his recognized language skills, Cist also printed a handful of titles in Latin and French.17

After 1800, Cist's printing decreased dramatically-generally he printed only the annual almanac and one other item from 1801 to 1805. These years represent the printer's opening a Washington office and introduce an inaccuracy in Cist's DAB entry.18 His biographer, Reginald C. McGrane, mentions that Cist was appointed public printer during the administration of President John Adams (1787-1801). This fact later emerged in the historical volume of Who Was Who, Appleton's Cyclopedia of American Biography, and several other biographical compilations. This inaccuracy is also cited in H. Benjamin Powell's Philadelphia's First Fuel Crisis, a history of the anthracite market in Pennsylvania. But neither Thomas nor McMurtrie make mention of Cist as a public printer, although both indicate he set up a printing operation in Washington. Leonard White's massive The Federalists: A Study in Administrative History, 1789-1801, makes no mention of Cist. In fact, there was no public printer until 1861. Cist did some government printing work, both in Philadelphia and later in Washington. Cist's imprint appeared on two copies of Post Office regulations, one printed in Philadelphia in 1798 (34904) and one in Washington in 1800 (38801). He undoubtedly contracted for other government printing, a powerful cog in the patronage machinery. For the 223 government imprints listed in Evans for 1799, 173 (77 percent) were unassigned. Only the postal laws (Evans 38801) carried Cist's imprint, and only twenty-five included a Washington imprint; Cist's and two other entries are the only ones assigned to a particular printer. The majority of the 173 unassigned entries were congressional bills or broadsides, and Cist more than likely contracted for some of this government work, but Cist was not the public printer.

I am categorizing information and I shall post it on up coming blogs.

Andrew C. Allen 6/21/13

513.638.7140

pewabic34@gmail.com

Thursday, June 20, 2013

The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America

The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, Vol. 85:1, March 1991 (ISSN 0006-128x) was a rich source of information about Charles Cist. A special thanks to Mr. William S. Peterson, editor, and Mr. Boyd Childress who wrote the article about Mr. Cist, pages 72-81.

Charles Cist, Philadelphia Printer

Boyd Childress

The German press in Pennsylvania, indeed with its Sowers and their large establishment, its bruderschaft of the Ephrata Monastery, its Armbruester, its Steiner, and a score more of intelligent printers, offers a phenomenon for reflection and study.1

Noted printing historian Lawrence Wroth thus introduced German printers in the state of Pennsylvania in his now classic The Colonial Printer. Among Wroth's "score more" was Charles Cist, who operated a printing business in Philadelphia from the early revolutionary period into the nineteenth century. While his printing output was modest when compared to contemporary Philadelphians Matthew Cary, Benjamin Franklin Bache, David Hall, or Francis Bailey, Cist printed both in English and German and was considerable factor in the history of printing in Philadelphia during his career. While the history of printing in the then-largest city in America has been well documented in various sources, there seems to be very little accurate biographical information on Cist and his printing. His entry in the Dictionary of American Biography 2 is both incomplete and inaccurate, and this brief sketch attempts to make use of additional primary material to supplement what we know about Cist and correct the DAB entry , which has found its way into other secondary biographical compilations, as well as scholarly historical research.

Charles Cist was born on 15 August 1738, in St. Petersburg, Russia.3 His education was extensive, including training in pharmacy and a medical degree from the University at Halle. With this background in the healing arts, Cist emigrated to the American colonies in 1769. Cist landed first in New York but settled immediately in Philadelphia. According to William McCulloch, who provided a significant addendum to Thomas' History of Printing in America "Cist tried many an earnest endeavor to discover the philosopher's stone" before he finally turned his attention to printing.4 Cist's name was a derivative of his given Russian name Carl Jacob Sigismund Thiel. With his new name, he first entered printing as a translator for the German printer Henry Miller.

In Philadelphia, he joined a sizable German community in a city of over 25,000, and after learning his new trade rapidly, Cist entered partnership with Melchior Steiner (or Styner), a native of Switzerland, in 1775. For the next six years, the firm printed fewer than fifty titles, but we do know from the records of the Pennsylvania colonial legislature that the two did considerable public printing. For example, Steiner and Cist were paid L 175 for "printing" in October 1777, the second year of their partnership. For the fall of 1780, the firm earned slightly less than L10,000 for public printing.5 The legislative council approved various payments for services provided on an inconsistent basis, and these payments present bills presented over an extended period of time. The last entry for Steiner and Cist came in December of 1782, over a year after the partnership dissolved. The firm also did considerable printing work for the Continental Congress. As early as 1776 they were paid $130 for providing paper and printing Congressional minutes-the paper was for loan office notes, and the minutes, yet unpublished, were bought by fellow-printer Robert Aiken. In 1777, Steiner and Cist were paid for printing 1,000 copies of a German-language revolutionary address to New Yorkers (Evans 15471). A unique episode in 1779 centered on an over payment for printing 1,300 copies of Observations on the American Revolution (Evans 16625), a propaganda document intended to support the colonial war effort. The journals of Congress record a payment of nearly $3,000 to Steiner and Cist in April, but a three-member committee was appointed the next month to investigate the possible over payment and the warrant was stopped. In June, the committee reported back to Congress and the account was settled for $971. A final example of Steiner and Cist's Congressional printing was a $200 payment in November of 1779.6 Nevertheless, the success of the firm of Steiner and Cist (or any printer, for that matter) cannot be measured by the record of its imprints. Indeed, printers such as Cist derived the majority of their income from peripheral or job printing, such as public printing and the sale of paper.

When Cist and Steiner first established their business, they were housed on Second Street near Arch Street, in the immediate proximity of most of the city's other printers. In late 1778, business had improved enough so they could move a block south on Second to the corner at Race Street.7 The most prominent (and profitable) of their imprints was Thomas Paine's The American Crisis (Evans 14953), printed in 1776 both in English and German (Evans 14963). The following year the firm printed the next three parts of Paine's political treatise. Steiner and Cist also printed an annual German language almanac beginning in 1779, a practice Cist continued until his death; Steiner likewise printed an almanac until 1797. Another printing staple was the newspaper , which the two published in partnership. Both Cist and Steiner published their own separate newspaper after the partnership dissolved. These were also German-language ventures.

Cist and Steiner dissolved their partnership in early 1781. McCulloch contends Steiner's laziness, negligence, and indifference led to their breakup. McCulloch also said Steiner had a drinking problem. While Cist remained in business under his name only, Steiner entered into another joint operation with Heinrich Kammerer, printing and selling books almost exclusively in German. While Steiner and Cist existed, it printed forty-seven separate titles; of these, fifteen (32 percent) were in German.8 Cist used this experience to launch the remainder of his successful printing career.

Cist moved his operation to Market Street when he and Steiner parted ways and stayed there until 1784, when he moved to the corner of Fourth and Arch Streets. In 1787, he was operating on Race Street, between Front and Second Streets. After 1791, he settled 104 Second Street near the corner of Race. These moves do not represent significant changes: these were addresses where several of the city's printers had shops. They do show Cist on the move for the best location for his business.

Cist married in 1781 and had two sons. Charles Cist, the elder, was an author and later, editor in Cincinnati, were he gained some literary notoriety. Another son Jacob, entered his father's printing business; worked in a shop his father established in the new Washington City after 1800; and finally settled in Wilkes-Barre as a postmaster, a position he held for most of the rest of his life. Jacob, an amateur naturalist, also got involved in a mining venture as his father had.

After the dissolution of his partnership with Steiner, Cist's book printing work increased. He printed Americanischer-Stadt und Land Calendar from 1782 until his death in 1805. His wife supervised the printing of the almanac in 1806. In 1806, the volume was published annually until 1860, a complete run of seventy-eight years. He seems to have been involved in publishing several German-language newspapers, although none on a regular basis. In 1786, he was one of several Philadelphians, including Matthew Cary, Thomas Sedden, William Spotswood, and James Trenchard, who sponsored the Colombian Magazine (Evans 21007), a short-lived effort.9 Cist also printed at least one issue of a newspaper in Washington in 1800. It, too, was a failure. Evidence attests to his reputation as a printer, as do the remarks of at least two contemporary printers. Isaiah Thomas notes, "Cist pursued it {printing} prudently, and acquired considerable property." McCulloch concludes, "Cist acquired property by marriage, and increased it by industry." In his printing history, Douglas McMurtrie makes occasional mention of Cist.10 But the highest praise of Cist's printing is from the federal Congress, noted Federalist Timothy Pickering, and prominent lexicographer Noah Webster. In the fall of 1785, Congress seriously considered Cist's proposal for printing the body's journals.

1. Lawrence C. Wroth, The Colonial Printer (Charlottesville: Dominion Books, 1964), pp. 261-62.

2. Reginald C. McGrave, "Cist, Charles," Dictionary of American Biography (New York: Scribners, 1930), II, 108.

3. "Cist," DAB.

___________________________________________________________________

Boyd Childress (Librarian III, Auburn University Library , Auburn University , Ala. 36849-5606) is a History Bibliographer and Reference Librarian at Auburn University.

PBSA 85:1 (1991), pp. 72-81.

I have copied from the pages of this article and here are my additional notes to help fill in the blanks. When the article discusses Charles Cist's move to different locations in Philadelphia he was establishing friends and a network of business connections. For example, if this would help the scholarly community to know that Charles Cist eldest son Charles (Edward) Cist moved to Cincinnati and settled in College Hill, a suburb of Cincinnati. There is a family connection to the Cary family of College Hill. It is my connection that Matthew Cary had family and with the elder Cist moved to Cincinnati together. This was in part due to the printing connection in Philadelphia. The slogan "Go West Young Man" might have been a factor. The Cary sisters were prolific poets in Cincinnati.

Furthermore, the reference to Mr. Cist second son, Jacob, is only half his name. Lewis Jacob Cist was his full name. He also had one of the best autograph collections in the world at the time of his death. On reason why he held postmaster in Wilkes-Barre was to mail out autograph request, or some how get his target to respond to him, and he would be right there in the post office to collect his new autograph. The auction catalog of his collection is now a collector's item. An additional note, his brother Henry M. Cist, a well-documented Brigid er General of the Civil War and author of The Army of the Cumberland, painstakingly hand wrote the dollar amounts of each autograph that was sold. The auction took two days. His notes are in the bloggers private collection.

Finally, when the article talks about Mr. Cist getting married in 1781. He married Mary Weiss, the daughter of one of George Washington's commanders, General Jacob Weiss. This is his connection to getting printing contacts with the newly formed Continental Congress. On an upcoming blog, I can upload a Continental Congress dollar bill signed by Charles Cist.

Andrew C. Allen 6/20/13

513.638.7140

pewabic34@gmail.com

Andrew C. Allen 6/20/13

513.638.7140

pewabic34@gmail.com

Tuesday, June 18, 2013

Wayne State University Find

My last visit to Wayne State University at the Purdy/ Kresge library was a very positive experience. The librarians there are very supportive of scholarly work and encourage the use of library equipment. They even took time to listen to my research and viewed this blog. Numerous avenues were found pertaining to the life of Charles Cist. I can tell my father new information about his life in USA that no one in the family knew about. There is a journal of hot air balloon rides that is in the rare book archives at Indian University, I found documentation of financial records of Cist and Steiner, information about a loosely knit network of early colonial printers formed by Benjamin Franklin, papers 1776-1805 (Historical Society of Pennsylvania -Johann Friedrich Ernst, 1748-1805).

Mr. Boyd Childress wrote a fantastic article in the Bibliographical Society of America. I need to arrange the material to correlate with my blog. His information will be in future blogs.

Part of my blogging experience is to update my reference skills by reviewing the APA reference- sixth edition and the MLA references- seventh edition. It is helpful to do as much work as possible before you go to the library just because other scholars want to use the same equipment.

Andrew C. Allen / June 13, 2013

513.638.7140

pewabic34@gmail.com

Mr. Boyd Childress wrote a fantastic article in the Bibliographical Society of America. I need to arrange the material to correlate with my blog. His information will be in future blogs.

Part of my blogging experience is to update my reference skills by reviewing the APA reference- sixth edition and the MLA references- seventh edition. It is helpful to do as much work as possible before you go to the library just because other scholars want to use the same equipment.

Andrew C. Allen / June 13, 2013

513.638.7140

pewabic34@gmail.com

Wednesday, May 29, 2013

A Possibility of New Scholarly Avenues

I am placing this scenario to scholars. Since the patriot printers, Cist and Steiner, translated and printed into German the first printing of the American Declaration of Independence, there could be a possibility that Cist and Steiner translated and printed the same and/or different documents in French and Russian and other languages. If Charles Cist did in fact translate and print the Declaration of Independence into Russian, would it be ironic for an escaped prisoner, who fond freedom in America, to then change his name and then send back to Russia( under the new name Charles Cist) a translated and printed copy of the American Declaration of Independence back to Russia. The ramifications of themes about liberty, imprisonment, and new life are endless. If this did indeed happen, Did the same authorities knew it was the same Charles Jacob Sigismund Thiel (Charles Cist) who escaped from under their control? If a scholar wants something to pursue, perhaps he/she can find other translated and printed forms of the American Declaration of Independence in other languages. A good place to start would be France and former Soviet Union.

Andrew C. Allen 5/29/13

513.638.7140

pewabic34@gmail.com

Andrew C. Allen 5/29/13

513.638.7140

pewabic34@gmail.com

Wednesday, May 8, 2013

Follow up on Declaration of Independence article

As I finished reading the article about the first translation and printing of the American Declaration of Independence in German, I went to a family reference guide. Henry M. Cist, the brother of Lewis J. Cist, hand noted in pen all the prices that each autograph and historical paper sold at auction from the Lewis J. Cist collection. The pen notations are on the left hand side of each page in the auction catalog from New York City. I probably do not have the only edition of the auction catalog, but I just might have the only edition that has all the prices from the collection. If this could be of benefit to other scholars, let me know. For example, an autograph of Abraham Lincoln went for twenty-five dollars ($25.00). I am currently checking if a copy of a German edition of the Declaration of Independence is in the auction catalog and, if so, how much it sold for. I am also sharing with scholars that through family stories that have been passed down that some of the collection went to the Smithsonian Institute, many Ivy League Universities along the east coast, private collectors, and European Universities. I will keep this blog posted of further findings.

Andrew C. Allen 5/08/13

513.638.7140

pewabic34@gmail.com

Andrew C. Allen 5/08/13

513.638.7140

pewabic34@gmail.com

Monday, May 6, 2013

A Historical First

This is an article that my friend Mr. John H. Trombley found on Charles Cist pertaining to the first generation of the translation and printing in German of the American Declaration of Independence. Just a note from family stories about the family (Lewis J. Cist) collection that was sold at auction in New York City by the executrix, Henry M. Cist, it appears to be a found from the collection that has been in a special rare collection at a college all these years. I wish to thank all the scholars who worked on this article and research . It is a joy to read. Here is the article.

The First Translation and Printing in German of the American Declaration of Independence

Karl J.R. Arndt

Clark University

When May E. Olson and I published the first volume of The German Language Press of the Americas, we were hopeful that new evidence of early German-American printing activities would turn up. I had continued to search for hidden documents when I launched the revision of Oswald Seidensticker's The First Century of German Printing in America, in cooperation with Dr. H. Vogt of the University of Gottingen under a grant of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. I am now able to present a major find which, after carefully weighing the circumstances of its creation, I consider the first printing of the Declaration of Independence in German, to be dated as early as July, 6, 1776.

The document, now in the special collections section of the Gettysburg College library, is a broadside measuring 16 inches by 12 3/4 inches, on ordinary laid paper without watermark, slightly damaged at the center through inept repair but clearly legible. At the bottom center it has the imprint, "Philadelphia: Gedruckt bey Steiner und Cist, in der Zweyten-strasse." The document was discovered by Werner Tannhof, a bibliographer from the University of Gottingen working for the Seidensticker project, with the help of Nancy Scott, Gettysburg College special collections librarian.

At first glance a comparison of this document with Henrich Miller's well-known printing on July 9th, shows great similarity, but a closer examination proves that the two printings are from different typesetting from different fonts. The translation in German also vary, although only slightly. These similarities and slight variations can readily be explained because both translations were most likely done by Charles Cist. On the authority of Isaiah Thomas we know that Cist was employed my Miller as his translator and by the printer's statement at the bottom of the broadside we know that Cist had a hand in the publication.

A sketch of Cist's life and activity in the Dictionary of American Biography informs us that he was born in 1738 in St. Petersburg, Russia.

Monatshefte, Vol. 77, No 2, 1985

0026-9271/85/0002/0138 $01.50/0

copyright 1985 by The Board of Regents of The University of Wisconsin System

Charles Cist came to America with a degree and skill that he earned from Halle University in Germany. It is very possible that he knew at least three languages, German, Russian, and English.

Andrew C. Allen 5/06/13

513.638.7140

pewabic34@gmail.com

The First Translation and Printing in German of the American Declaration of Independence

Karl J.R. Arndt

Clark University

When May E. Olson and I published the first volume of The German Language Press of the Americas, we were hopeful that new evidence of early German-American printing activities would turn up. I had continued to search for hidden documents when I launched the revision of Oswald Seidensticker's The First Century of German Printing in America, in cooperation with Dr. H. Vogt of the University of Gottingen under a grant of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. I am now able to present a major find which, after carefully weighing the circumstances of its creation, I consider the first printing of the Declaration of Independence in German, to be dated as early as July, 6, 1776.

The document, now in the special collections section of the Gettysburg College library, is a broadside measuring 16 inches by 12 3/4 inches, on ordinary laid paper without watermark, slightly damaged at the center through inept repair but clearly legible. At the bottom center it has the imprint, "Philadelphia: Gedruckt bey Steiner und Cist, in der Zweyten-strasse." The document was discovered by Werner Tannhof, a bibliographer from the University of Gottingen working for the Seidensticker project, with the help of Nancy Scott, Gettysburg College special collections librarian.

At first glance a comparison of this document with Henrich Miller's well-known printing on July 9th, shows great similarity, but a closer examination proves that the two printings are from different typesetting from different fonts. The translation in German also vary, although only slightly. These similarities and slight variations can readily be explained because both translations were most likely done by Charles Cist. On the authority of Isaiah Thomas we know that Cist was employed my Miller as his translator and by the printer's statement at the bottom of the broadside we know that Cist had a hand in the publication.

A sketch of Cist's life and activity in the Dictionary of American Biography informs us that he was born in 1738 in St. Petersburg, Russia.

Monatshefte, Vol. 77, No 2, 1985

0026-9271/85/0002/0138 $01.50/0

copyright 1985 by The Board of Regents of The University of Wisconsin System

Charles Cist came to America with a degree and skill that he earned from Halle University in Germany. It is very possible that he knew at least three languages, German, Russian, and English.

Andrew C. Allen 5/06/13

513.638.7140

pewabic34@gmail.com

Tuesday, April 16, 2013

The Escape Continued

Charles had another experience that the guards did not know about. He recalled that his mother use to take him to the reptile house at the little zoo when you was young. Thursdays were his favorite visits, because that was feeding day for the snakes. He remembered from his youth that it took about fifteen minutes for a snake to strike and slowly gnaw a mouse into its dislocated jaw to swallow. A rattlesnake cannot bite if it is in the middle of eating a field mouse, or rat. Charles suspected the dead man from the cell was in too much in a hurry and could not get his hand out quickly enough to avoid the poisonous bite.

The guards must have fed the snake when Charles was outside during his afternoon fresh air excursions. That is the only explanation he could think of as to how the snake survived the winter months. The riddle was making sense. He knew he had to find a mouse to feed the rattlesnake before the guards gave it a meal.

Charles thought of a clever way to catch a field mouse. He would lie down in the grass and pray that a mouse would smell the aroma from the smelly cheese in his pocket. He did this for weeks. Finally, as he lay on his back he took a cup from his cell room and slowly lowered it onto a field mouse that was chewing the stale cheese from his pocket. Now he had another key to the safe, but a few questions remained. One, what was behind the rattlesnake in a red velvet bag? Two, how was he going to get past the guard and enter the streets of St. Petersburg? He contemplated this for a week.

Later, the guard slipped some timely news to Charles. The stage coach to Siberia was leaving on Monday, and he had orders to put Charles on the coach. This was certain death, because if you leave for Siberia you do not return. The government puts you in a work camp and works you until you literally fall down to your death. He decided to find out what was in the red velvet bag on Sunday night, the beginning of a new week. A new chapter was soon to be written. It was sink, swim, or be bitten. Charles opened the first key, the wooden horizontal panel. Then the mouse dropped into the box and the snake swallowed the creature giving Charles about fifteen minutes to remove the red velvet bag from the box that housed the snake which was the second key. The third key stumped Charles for a long time that evening. He remembered what the royal court told him just before his incarceration, that HRH Catherine the Great would not tell him the answer. He knew that what the Queen said was rule. Charles went to the door and opened it. Looking back inside the prison cell, he noticed a full moon resting perfectly inside the frame of the window on the south wall. He knew it was about two in the morning by now. It was time to see the contents of the velvet bag from the snake pit which contained all the gems that belonged to Charles in the first place! He smiled and laughed as he tiptoed past the guard. Then he paused knowing that if he left quietly, he would surely get the guard to gather his team of guards to chase after Charles. He could not believe what he was going to do. Without saying a word, he gently got down on his knees and woke the guard. He quickly took one of the smaller diamonds and placed it in the guard's hand and clasped all fingers together into a ball. He was betting that the royal court would let him go free if he had the smarts to retrieve his own gem collection. The guard smiled and went back to sleep without making a sound.

Charles had just minutes to maneuver around town to get to the station before sunrise. He knew the stage coach routes and times. It was this time during his escape that he changed his name from Charles Jacob Sigismund Thiel to Charles Cist. He took the C from Charles, the J in Latin became an I, S from Sigismund, T from Thiel, thus the surname Cist was born. This proved to be beneficial because the authorities were looking for Mr. Thiel that ends with a T. The new name Cist shuffled him to different alphabetical groups when rounded up during check points through out Europe looking for fugitives. (My father mentioned that any person in the world is directly descended from Charles Cist)

Andrew C. Allen 4/16/13

513.638.7140

pewabic34@gmail.com

The guards must have fed the snake when Charles was outside during his afternoon fresh air excursions. That is the only explanation he could think of as to how the snake survived the winter months. The riddle was making sense. He knew he had to find a mouse to feed the rattlesnake before the guards gave it a meal.

Charles thought of a clever way to catch a field mouse. He would lie down in the grass and pray that a mouse would smell the aroma from the smelly cheese in his pocket. He did this for weeks. Finally, as he lay on his back he took a cup from his cell room and slowly lowered it onto a field mouse that was chewing the stale cheese from his pocket. Now he had another key to the safe, but a few questions remained. One, what was behind the rattlesnake in a red velvet bag? Two, how was he going to get past the guard and enter the streets of St. Petersburg? He contemplated this for a week.

Later, the guard slipped some timely news to Charles. The stage coach to Siberia was leaving on Monday, and he had orders to put Charles on the coach. This was certain death, because if you leave for Siberia you do not return. The government puts you in a work camp and works you until you literally fall down to your death. He decided to find out what was in the red velvet bag on Sunday night, the beginning of a new week. A new chapter was soon to be written. It was sink, swim, or be bitten. Charles opened the first key, the wooden horizontal panel. Then the mouse dropped into the box and the snake swallowed the creature giving Charles about fifteen minutes to remove the red velvet bag from the box that housed the snake which was the second key. The third key stumped Charles for a long time that evening. He remembered what the royal court told him just before his incarceration, that HRH Catherine the Great would not tell him the answer. He knew that what the Queen said was rule. Charles went to the door and opened it. Looking back inside the prison cell, he noticed a full moon resting perfectly inside the frame of the window on the south wall. He knew it was about two in the morning by now. It was time to see the contents of the velvet bag from the snake pit which contained all the gems that belonged to Charles in the first place! He smiled and laughed as he tiptoed past the guard. Then he paused knowing that if he left quietly, he would surely get the guard to gather his team of guards to chase after Charles. He could not believe what he was going to do. Without saying a word, he gently got down on his knees and woke the guard. He quickly took one of the smaller diamonds and placed it in the guard's hand and clasped all fingers together into a ball. He was betting that the royal court would let him go free if he had the smarts to retrieve his own gem collection. The guard smiled and went back to sleep without making a sound.

Charles had just minutes to maneuver around town to get to the station before sunrise. He knew the stage coach routes and times. It was this time during his escape that he changed his name from Charles Jacob Sigismund Thiel to Charles Cist. He took the C from Charles, the J in Latin became an I, S from Sigismund, T from Thiel, thus the surname Cist was born. This proved to be beneficial because the authorities were looking for Mr. Thiel that ends with a T. The new name Cist shuffled him to different alphabetical groups when rounded up during check points through out Europe looking for fugitives. (My father mentioned that any person in the world is directly descended from Charles Cist)

Andrew C. Allen 4/16/13

513.638.7140

pewabic34@gmail.com

Monday, April 15, 2013

The Escape

Charles Jacob Sigismund Thiel had encountered a reversal of fortune. He had served as a doctor of medicine in the royal court of Catherine the Great in the mid 1700's. Now he found himself in a dark, damp, musty, prison cell in St. Petersburg, Russia. Fortunately, his youth and academic life at Halle University exposed him to live "outside the comfort zone" experiences that enabled him to survive his present situation inside a Russian cell.

The royal court had confiscated his gem collection; mostly diamonds, emeralds, and rubies. His prized possession, an eighteen carat diamond that was scheduled to be purchased for Catherine the Great had been confiscated during the coup. It was easier for the palace police just to take the collection which included thirty-seven diamonds totaling two hundred eighty-five carats. He wanted his collection back.

Riddles were more prevalent in Charles' day of the mid 1700's. The royal court gave Charles a riddle and if solved, he could use it to gain his freedom, collection, and a new life. If he failed; death. There were three keys to unlock the safe were the Halle diamond was kept. Charles nicknamed the diamond after his Alma mater, Halle University. Could he do it?

As he sat in his jail cell, he noticed a human skeleton in the corner of the dimly lit room, and when he paced the floor he heard rattling sounds appeared, but from where? He was let outside in the afternoon three times a week. After weeks of this routine and thinking about his surroundings and controlled timed schedules, he thought more about the riddle and how the dead body was a sign from the cell. The human carcass would be the first key to unlocking the safe. After an entire season of cold winter blahs, a guard inadvertently showed Charles a mouse that he kept in his pocket during the winter months. The mouse would become the second key to unlocking the safe. All of this information was in Charles's head, but he made no connections until the sunlight poured in from the window up above the south wall. The sun position had to go through an entire season before he could begin to put the pieces of the puzzle together. By this time, Charles had lost many pounds and lost strength in his left arm. On a Thursday afternoon, rays of light beamed close to the skeleton and he noticed the wall had a slight bump in it. Charles moved the bones away from the wall. Fresh foot-marks were on the floor. All this had become obvious because of the sunlight. He was stooped. Charles picked away at the wall and instead of peeling away and peeling downward, he picked at the wall and pulled towards him. After many turns, this repeated motion revealed a horizontal wooden panel that was painted black. This explained why it blended into the darkness. Over time, the moisture had warped the wood to expose the box. As he pulled the horizontal panel towards him, a lever pulled a box down to the ground. The box had a black hole on top of it and a clear panel in which you could peer into it. A rattlesnake coiled dead center stared at Charles. From his observations, he could see that the coiled mesh on top of the box served as a mechanism. It became clear to him after awhile that if you place your hand in the coiled mesh from above and tried to remove your hand quickly, the mesh would tighten and the hand would stay suspended long enough for the rattlesnake to strike a deadly, poisonous bite. Charles assumed this is what had happened to the dead gentleman that shared his prison cell. He knew he had to be careful. He slowly pushed the horizontal wooden box back into the wall and the snake filled box disappeared.

I have an appointment. I will resume The Escape again.

Andrew C. Allen 4/15/13

513.638.7140

pewabic34@gmail.com

The royal court had confiscated his gem collection; mostly diamonds, emeralds, and rubies. His prized possession, an eighteen carat diamond that was scheduled to be purchased for Catherine the Great had been confiscated during the coup. It was easier for the palace police just to take the collection which included thirty-seven diamonds totaling two hundred eighty-five carats. He wanted his collection back.

Riddles were more prevalent in Charles' day of the mid 1700's. The royal court gave Charles a riddle and if solved, he could use it to gain his freedom, collection, and a new life. If he failed; death. There were three keys to unlock the safe were the Halle diamond was kept. Charles nicknamed the diamond after his Alma mater, Halle University. Could he do it?

As he sat in his jail cell, he noticed a human skeleton in the corner of the dimly lit room, and when he paced the floor he heard rattling sounds appeared, but from where? He was let outside in the afternoon three times a week. After weeks of this routine and thinking about his surroundings and controlled timed schedules, he thought more about the riddle and how the dead body was a sign from the cell. The human carcass would be the first key to unlocking the safe. After an entire season of cold winter blahs, a guard inadvertently showed Charles a mouse that he kept in his pocket during the winter months. The mouse would become the second key to unlocking the safe. All of this information was in Charles's head, but he made no connections until the sunlight poured in from the window up above the south wall. The sun position had to go through an entire season before he could begin to put the pieces of the puzzle together. By this time, Charles had lost many pounds and lost strength in his left arm. On a Thursday afternoon, rays of light beamed close to the skeleton and he noticed the wall had a slight bump in it. Charles moved the bones away from the wall. Fresh foot-marks were on the floor. All this had become obvious because of the sunlight. He was stooped. Charles picked away at the wall and instead of peeling away and peeling downward, he picked at the wall and pulled towards him. After many turns, this repeated motion revealed a horizontal wooden panel that was painted black. This explained why it blended into the darkness. Over time, the moisture had warped the wood to expose the box. As he pulled the horizontal panel towards him, a lever pulled a box down to the ground. The box had a black hole on top of it and a clear panel in which you could peer into it. A rattlesnake coiled dead center stared at Charles. From his observations, he could see that the coiled mesh on top of the box served as a mechanism. It became clear to him after awhile that if you place your hand in the coiled mesh from above and tried to remove your hand quickly, the mesh would tighten and the hand would stay suspended long enough for the rattlesnake to strike a deadly, poisonous bite. Charles assumed this is what had happened to the dead gentleman that shared his prison cell. He knew he had to be careful. He slowly pushed the horizontal wooden box back into the wall and the snake filled box disappeared.

I have an appointment. I will resume The Escape again.

Andrew C. Allen 4/15/13

513.638.7140

pewabic34@gmail.com

Thursday, April 4, 2013

Oral traditions transformed into a blog.

My father and I have had many conversations about the life of Charles Cist. As a young boy growing up, it was not so much a conversation, but me just listening to his stories about his ancestors. My father worked at a law firm for forty years. I am thankful that he was home every night to share family time with his children. He taught me the importance of the oral history traditions and the validity of family history passed down from generation to generation. As he approaches his eighty-fourth birthday, it is still a pleasure to talk with him about Charles Cist. It is a connection that we have together. Now it is my turn to share questions about Charles Cist with my father. I share my questions, for example, did Charles Cist have any brothers, or sisters in Russia? Is there a side of the family over in Russia today that is thinking the same about us? Has there been an oral history passed down from a Russian family about an uncle that escaped to America? Perhaps, this blog can connect stories, reunite/start relationships, answer puzzles.

There are some challenges that I want to over come. Charles Cist had children. One of them was Lewis J. Cist from Cincinnati, OH, no offspring. He was a little eccentric When he passed away he had perhaps the largest and best autograph collection in the world. The collection had autographs from poets, world leaders (ancient and new), signers of the Declaration of Independence, and so much more. The auction catalog is now a collector's item. Moving forward, the collection was settled and the proceeds were placed in a Cincinnati bank. The bank went under with the business cycles of financial depressions and prosperity of the 1800's. Well, it was told to me that the other side of the family on the East coast blames our side for the loss and the two sides have not been in communications for a very long time. Hopefully, the internet can get people talking and helping to complete the story of Charles Cist. People should realized that I was not even around during the 1800's and I had nothing to do with the outcome. Hopefully, this will work in my favor. As the older generation passes away, this can be an extension of a conversation in word art. Once again we are dealing with a life story that encompasses the ideals about freedom and painting a story about a man of individual freedom struggles, but also spent his life with the printed forms of educating patriots during the American Revolution. The printers of Cist and Steiner's most famous printed pamphlet was Thomas Paine's Common Sense.

I will share my creative writing. I will specify that I am in dream mode. Dream mode is when I can imagine what could have happened based on the history that has been passed down. I will state the separations for the bloggers. For example, history has been passed down that Charles Cist escaped from Russia during the coup of Catherine the Great's reign. How did he escape? Who did he encounter? How long did it take him to reach America? How did he end up marrying General Jacob Weiss's daughter? General Weiss was a general under George Washington. These are a few of the questions that I have for this blog.

My next blog will deal with the Great Escape from prison and evading a long, lonely ride to Siberia.

Andrew C. Allen 4/4/13

513.638.7140

pewabic34@gmail.com

There are some challenges that I want to over come. Charles Cist had children. One of them was Lewis J. Cist from Cincinnati, OH, no offspring. He was a little eccentric When he passed away he had perhaps the largest and best autograph collection in the world. The collection had autographs from poets, world leaders (ancient and new), signers of the Declaration of Independence, and so much more. The auction catalog is now a collector's item. Moving forward, the collection was settled and the proceeds were placed in a Cincinnati bank. The bank went under with the business cycles of financial depressions and prosperity of the 1800's. Well, it was told to me that the other side of the family on the East coast blames our side for the loss and the two sides have not been in communications for a very long time. Hopefully, the internet can get people talking and helping to complete the story of Charles Cist. People should realized that I was not even around during the 1800's and I had nothing to do with the outcome. Hopefully, this will work in my favor. As the older generation passes away, this can be an extension of a conversation in word art. Once again we are dealing with a life story that encompasses the ideals about freedom and painting a story about a man of individual freedom struggles, but also spent his life with the printed forms of educating patriots during the American Revolution. The printers of Cist and Steiner's most famous printed pamphlet was Thomas Paine's Common Sense.